Introduction: The Modern Journey of Shodo Japanese Calligraphy

As we explored in the previous column, shodo Japanese calligraphy has deep roots in ancient and medieval history. From sutra copying to court poetry, each era shaped how ink and brush expressed Japanese culture. In this column, we follow its evolution from the late Edo period to the present — a time of literacy booms, Western influence, modern art movements, and global interest in Japan and culture.

From bustling merchant towns to contemporary galleries, shodo and sumi e have continually adapted. The story of this evolution shows how a traditional art can survive modernization and still feel fresh to today’s viewers, collectors, and Japanese artists.

From Edo Towns to a Modern Nation

Late Edo Period: Popular Culture and the Rise of Literacy

In the late Edo period (18th–19th century), calligraphy became deeply woven into everyday life. As literacy spread among merchants, artisans, and townspeople, brush writing shifted from elite skill to social norm. Children learned to write in terakoya, local temple schools where practical writing and calligraphic style were taught side by side.

Shops used bold Edo-style characters on signboards, kabuki theaters printed program titles in dynamic scripts, and poetry gatherings displayed hanging scrolls combining verse with expressive lines. Calligraphy appeared on ukiyo-e prints, envelopes, and decorative goods, blurring the line between “useful writing” and shodo Japanese calligraphy as popular culture.

Meiji Period: Western Influence and Cultural Reevaluation

The Meiji Restoration (1868–1912) brought rapid modernization and Westernization. Pens, pencils, and the Roman alphabet entered government, science, and business. For a time, some feared that traditional brush writing would lose its place.

Yet the same era also sparked a strong desire to protect Japanese culture. Educators and thinkers began to frame shodo as part of the nation’s artistic heritage. Calligraphy was formally included in public education, and cultural leaders such as Okakura Tenshin argued that traditional arts — including calligraphy, tea ceremony, and ink painting — carried a spiritual dimension that industrial modernity could not replace.

In this tension between Western techniques and Japanese culture, shodo Japanese calligraphy started to be seen not only as a tool for writing but as an art that expressed the character of the nation.

Taisho and Showa: Shodo, Sumi e, and Modern Art

Calligraphy as Fine Art in a Changing Japan

During the Taisho and early Showa periods (1912–1945), Japanese calligraphy moved more clearly into the realm of fine art. Exhibitions, study groups, and art journals began to feature calligraphy alongside painting and sculpture.

Some calligraphers emphasized classical scripts and strict technique, while others experimented with composition, scale, and abstraction. They rethought how characters could fill a page, how white space could hold tension, and how a single stroke could carry as much emotion as a full landscape in sumi e.

These artists drew on global modern art trends, including abstraction and expressionism, while staying grounded in brush, sumi ink, and washi paper. The result was a new visual language that connected shodo to contemporary art without severing it from its origins.

Showa to Postwar: Groups, Exhibitions, and New Movements

In the mid-to-late Showa period, calligraphy associations formed and large-scale exhibitions became more common. Artists developed distinct personal styles, from powerful, thick strokes to delicate, almost musical lines.

Some movements aimed to purify shodo Japanese calligraphy by returning to earlier models, while others pursued “avant-garde calligraphy,” breaking characters apart or pushing them toward near-abstract forms. In both directions, the goal was the same: to keep calligraphy alive as a serious art form in a rapidly changing society.

Postwar and Contemporary: Global Japanese Artists and New Media

Postwar Era: Globalization and the Spiritual Return to Shodo

After World War II, Japan opened even more strongly to global influences. Abstract expressionism, graphic design, and modern architecture all affected how artists thought about space, gesture, and line. Some calligraphers began to create works where legibility was secondary and visual impact was primary, using oversized brushes, experimental papers, and unconventional layouts.

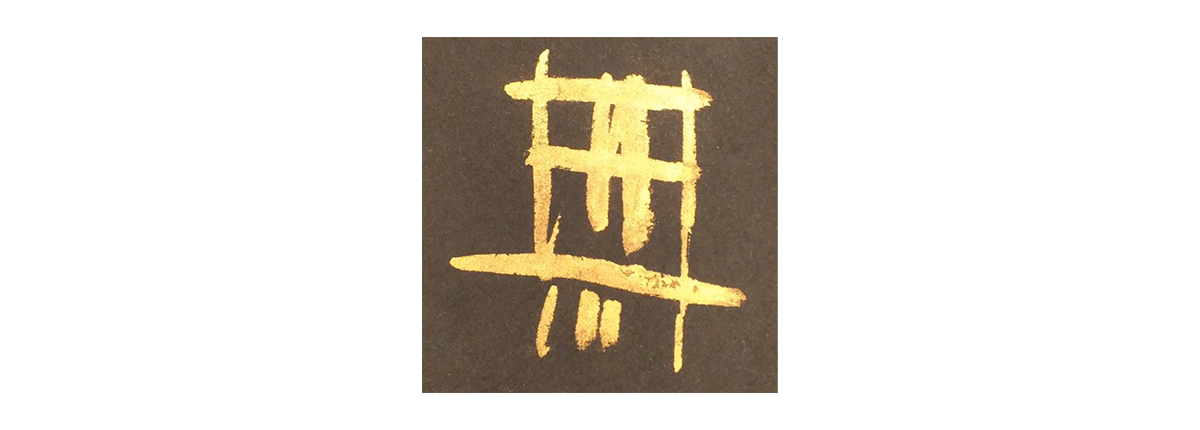

At the same time, many artists and teachers returned to the spiritual roots of shodo. They emphasized the connection between calligraphy, Zen practice, breathing, and mindfulness. Writing a single character became an exercise in presence: a way to align body and mind, independent of religion but resonant with centuries of Buddhist and Zen tradition.

These two directions — experimental and spiritual — continue to define the postwar evolution of shodo Japanese calligraphy.

Contemporary Japanese Calligraphy: Tradition in Motion

Today, Japanese calligraphy lives in multiple worlds at once. It is part of school education, where children still learn to handle brush and sumi ink. It is a respected field of fine art, seen in galleries and museums. And it is a visual resource for branding, architecture, fashion, and digital design.

Contemporary Japanese artists explore new materials and platforms: metallic pigments, layered papers, installations that fill entire rooms, and digital projections of brushstrokes moving across walls. Others focus on quiet, small-scale works that echo the intimacy of handwritten letters and Zen scrolls.

Workshops around the world invite people to experience shodo and sumi e as hands-on introductions to Japanese culture. For many visitors, the first time they hold a brush in a Japanese studio becomes a defining memory of their encounter with Japan and culture.

Conclusion: Writing the Future with Ancient Lines

The modern history of Japanese calligraphy — from late Edo through Meiji, Taisho, Showa, and into the present — is a story of resilience, reinvention, and rediscovery. Edo merchants, Meiji educators, avant-garde artists, and today’s global practitioners have all shaped how shodo Japanese calligraphy looks and feels.

Even in a high-tech world, the stroke of a brush on paper can still slow the viewer’s breathing and focus the mind. That is why collectors and learners continue to seek out original works and workshops: each piece carries not only ink and paper, but also the layered history of Japanese culture and the individual spirit of the Japanese artist who made it.

Coming up in Column #5: “The Spirit of the Brush – Exploring the Zen Philosophy Behind Shodo,” we will look more closely at how ideas from Zen and meditation shape the way artists move, pause, and breathe through each line.

deepens your connection to Japanese tradition.

Explore and purchase hand-selected Japanese calligraphy artworks:

https://calligraphyartwork.stores.jp/

コメント