Introduction: A Cultural Legacy Written in Ink

Japanese calligraphy, known as shodo Japanese calligraphy, has a long history that begins with Chinese ink and grows into something distinctly Japanese. It arrived from the continent together with Buddhism, governmental systems, and kanji, then gradually transformed into an art form that expresses Japanese culture in a uniquely local way.

Today, brush and ink belong not only to temples and museums but also to classrooms, galleries, design studios, and the homes of collectors. Calligraphy is widely recognized as one of Japan’s traditional arts, practiced with the classic “Four Treasures” — brush, sumi ink, inkstone, and paper — yet constantly renewed by each Japanese artist who picks up the brush.

Historical Roots of Shodo Japanese Calligraphy

Ancient Origins: Kanji, Buddhism, and the First Brushes

The story begins in the 5th–6th centuries, when Chinese characters and calligraphic methods reached Japan along with Buddhism and other elements of statecraft. Early calligraphers copied Chinese sutras and official documents, training themselves to follow continental models as closely as possible. Over time, these imported characters became kanji, the foundation of the written language in Japan.

At this stage, Japanese calligraphy still looked very Chinese. The goal was accuracy and elegance according to the standards of masters on the continent. But the seeds of something new had already been planted: a different language, a different grammar, and a different sense of rhythm waiting to shape the lines.

Nara Period: Script as Sacred Practice

During the Nara period (710–794), calligraphy was closely tied to Buddhism. Copying sutras by hand with a brush and sumi ink was considered a meritorious act, a form of devotion and meditation. The focus was not only on legible characters but on the sincerity behind each line, written slowly and carefully on paper prepared for ritual use.

This idea of writing as spiritual practice still echoes today in shodo Japanese calligraphy and sumi e, where a few strokes can express intention, concentration, and respect for the moment.

Heian Period: Kana, Court Culture, and a Japanese Style

During the Heian period (794–1185), calligraphy began to separate from its Chinese roots. This era saw the creation and spread of kana — the hiragana and katakana syllabaries — which made it possible to write the Japanese language more directly and with greater fluidity. Court nobles used a combination of kanji and flowing kana to compose poetry, diaries, and letters, laying the groundwork for a truly Japanese style.

Influential calligraphers such as Ono no Tōfū and his contemporaries are often described as central figures in establishing a Japanese-style calligraphy. Their work emphasized grace, rhythm, and the emotional tone of the line, not only technical correctness. This shift mirrored a broader cultural movement in which the court sought its own voice in literature, painting, and other arts — a turning point for both shodo Japanese calligraphy and the wider story of Japan and culture.

Medieval Japan: Zen, Sumi e, and Expressive Simplicity

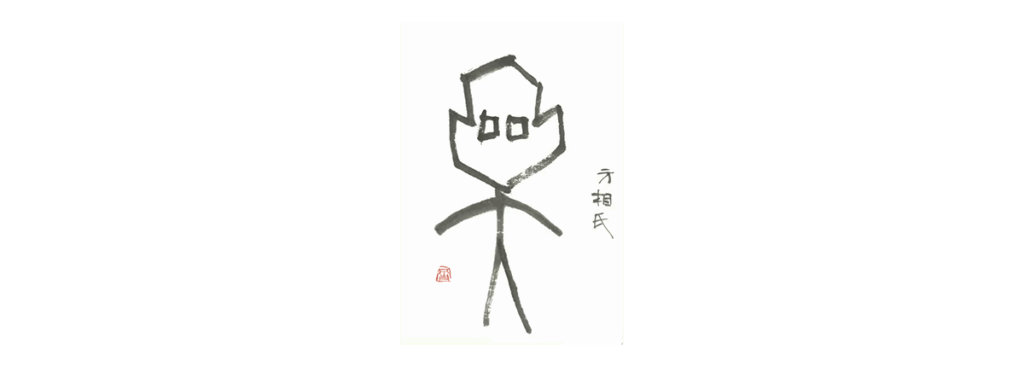

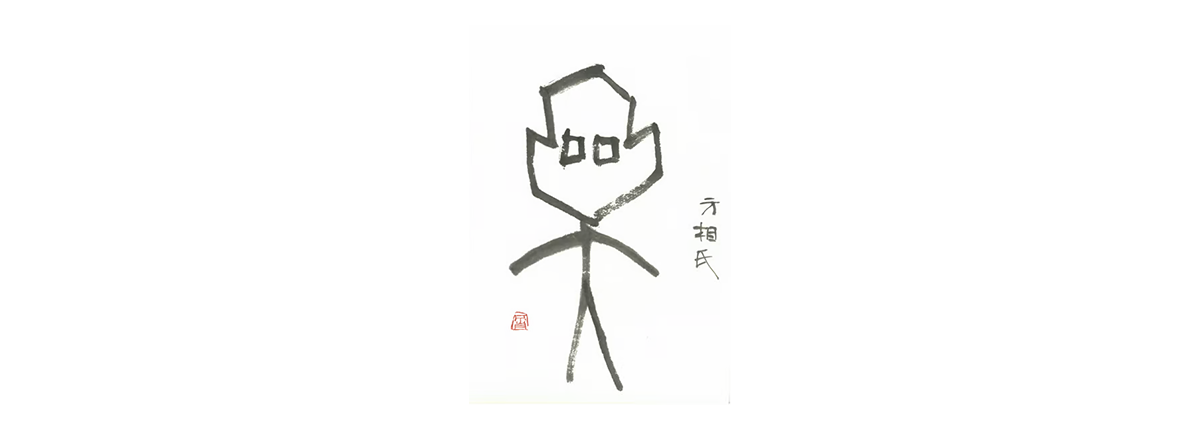

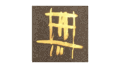

In the Kamakura and Muromachi periods (1185–1573), Zen Buddhism reshaped the way calligraphers thought about ink. Monks brushed short phrases, poems, or a single character in a style later called bokuseki (“ink traces”), valuing directness and spiritual clarity over perfection. The brushwork could be rough, fast, and full of energy — a record of the mind at a single moment.

At the same time, ink painting, or sumi e, grew alongside calligraphy. Landscapes, bamboo, and plum blossoms were painted with the same tools and sensibility, reducing the world to a few essential strokes. The shared emphasis on spontaneity, negative space, and silence made shodo and sumi e twin paths into Japanese culture: one focused on characters, the other on images, both seeking spirit rather than surface detail.

Edo Period: Education, Edo Moji, and Everyday Writing

With the long peace of the Edo period (1603–1868), calligraphy spread far beyond the court and temples. In terakoya — local temple schools and private academies — children from merchant and artisan families practiced brush writing as part of basic education. Good handwriting became a sign of discipline and refinement, not only for nobles but for townspeople as well.

Specialized styles known as Edo moji (“Edo characters”) appeared on shop signs, kabuki theater billboards, and sumo wrestler name boards. These bold, decorative forms showed how shodo Japanese calligraphy could support commerce and popular entertainment, not just religious or literary culture. The art was on the street as much as it was in scrolls.

From Meiji to the Present: National Art in a Global World

In the modern era, from Meiji onward, calligraphy was folded into the national school curriculum and promoted as both an artistic discipline and a way to cultivate character. Exhibitions, study societies, and professional associations emerged, and the idea of calligraphy as a “national art” took shape alongside other traditional arts such as tea ceremony and ink painting.

Today, shodo is practiced by students in Japan and by learners and collectors worldwide. Contemporary Japanese artists mix classical scripts with experimental layouts, color washes, and even digital media. Calligraphy appears in museum shows, luxury branding, anime title designs, and global workshops where visitors discover how a single stroke of sumi ink can reshape their sense of time and attention.

Why This History Matters for Today’s Shodo

Understanding this arc — from imported kanji to a homegrown art form — changes how we see each brushed character. When you watch a Japanese artist pick up the brush, you are not only seeing a personal style; you are seeing traces of Buddhist sutra-copying, Heian court poetry, Zen ink traces, bustling Edo streets, and modern design thinking in motion.

For anyone exploring Japanese culture, especially those drawn to shodo Japanese calligraphy and sumi e, history is not just background. It is part of what you hang on your wall or hold in your hands: centuries of practice distilled into a few strokes. That is what makes Japanese calligraphy feel like both an ancient tradition and a contemporary language of line — a living bridge between Japan and culture seekers around the world.

deepens your connection to Japanese tradition.

Explore and purchase hand-selected Japanese calligraphy artworks:

https://calligraphyartwork.stores.jp/

コメント