Introduction – Why Prince Shōtoku Matters to Shodo Japanese Calligraphy

When people search for shodo Japanese calligraphy or “Japan and culture,” they often encounter elegant scrolls and Zen phrases, not political history. Yet at the root of Japanese calligraphy stands a statesman: Prince Shōtoku (Umayado no Ōji), a semi-legendary regent of the Asuka period (6th–7th century) who helped shape Buddhism, government, and the written word in Japan.

For Shōtoku, writing with brush and sumi ink was more than administration. It was a way to express Buddhist philosophy, define national identity, and align Japan with the high cultures of East Asia. Without his decisions, Shodo Japanese calligraphy might never have become the refined art of mind and line that it is in Japanese culture today.

Prince Shōtoku in the Asuka Period – Statesman, Reformer, Cultural Architect

Buddhism, Government Reform, and the Written Word

Prince Shōtoku is famous for promoting Buddhism, introducing the Seventeen-Article Constitution, and helping centralize the Yamato state under Empress Suiko. In all of these reforms, written language—kanji imported from China—played a central role.

Scripture, law codes, diplomatic letters, and temple records all required calligraphic skill. Instead of treating writing as a minor technical ability, Shōtoku positioned it as a pillar of good government: a way to record intention, articulate ethics, and stabilize authority. This move set the stage for later Japanese artists and officials who would see brushwork as both discipline and expression.

The Hokke Gishō – Early Japanese Thought in Ink

Lotus Sutra Commentary and the Formation of Intellectual Japan

A key work traditionally attributed to Prince Shōtoku is the Hokke Gishō, a commentary on the Lotus Sutra. Many scholars regard it as Japan’s oldest surviving book and one of the earliest examples of Japanese engagement with Buddhist philosophy in written form.

Written in a kaisho-style script influenced by Chinese models, this text is more than religious commentary. It shows an early Japanese intellectual using kanji to organize thought, argue ideas, and guide readers. For shodo Japanese calligraphy, this is crucial: it demonstrates that from the beginning, brushwork in Japan was tied to interpretation, not mere copying. Calligraphy here becomes a vehicle for reasoning, not only ritual.

Kanji, Sumi, and the Birth of a Literary Culture

The Hokke Gishō also illustrates how kanji, sumi ink, and religious learning came together to form a new literary culture in Japan. As sutra copying spread to temples and court circles, the act of writing itself became a spiritual practice: each character an offering, each brushstroke a form of meditation.

This ethos would later influence everything from Zen calligraphy to modern sumi e ink painting, where the same tools—brush, ink, and washi paper—are used to reveal the “mind behind the line” in both image and script.

Diplomacy and Calligraphy – Envoys, Letters, and Identity

From the Land of the Rising Sun to the Land of the Setting Sun

Shōtoku’s vision was not limited to the monastery. He understood that Japan’s place in Asia also needed to be written into existence. In 607, he sponsored a mission to the Sui dynasty led by Ono no Imoko. The famous letter carried by this envoy opened with the line:

“From the Son of Heaven in the land where the sun rises,

to the Son of Heaven in the land where the sun sets.”

Written in classical Chinese characters, this message shocked the Sui court because it implied equality between the Japanese ruler and the Chinese emperor. The letter is often cited as the first written instance of Japan describing itself as the “land of the rising sun.”

From a calligraphic perspective, this moment is more than diplomatic theater. It shows how written characters—laid down in precise brushstrokes—could assert political identity and cultural confidence. Calligraphy, in this sense, was Japan’s first “soft power” tool.

Writing as Spiritual Practice in Early Japanese Culture

From Sutra Copying to “Calligraphy Is the Person”

Shōtoku’s devotion to Buddhist texts helped establish copying sutras as a major spiritual activity in early Japan. Monks and scribes used brush and ink to reproduce scriptures, believing that each stroke accumulated merit and purified the mind.

Out of this practice grew a core idea that later calligraphers would summarize as Sho wa hito nari—“calligraphy is the person.” The quality of one’s writing was seen as reflecting inner character, sincerity, and training. This principle still guides many Japanese artists today, whether they work in Shodo Japanese calligraphy, sumi e painting, or other ink-based arts rooted in Japanese culture.

Prince Shōtoku’s Ongoing Influence on Japanese Artists

From Semi-Legendary Regent to Cultural Icon

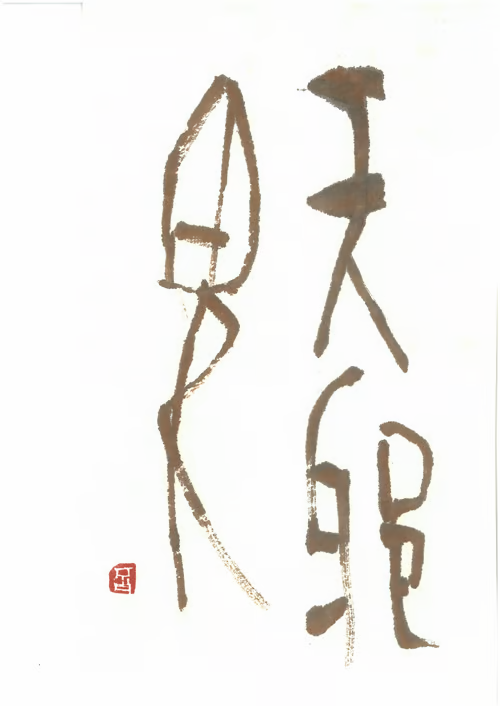

Over centuries, Prince Shōtoku became a semi-legendary protector of Buddhism and a symbol of enlightened rule. Temples, scrolls, and later artworks often depict him holding a sutra or brush, embodying the unity of spiritual insight and written expression.

For many contemporary Japanese artists and calligraphers, his story still resonates. He represents a moment when Japan chose to engage with continental culture on its own terms—importing kanji and calligraphic techniques, but gradually shaping them into something distinctively Japanese. For overseas readers searching for “Japan and culture,” his life offers a powerful entry point into how writing, belief, and statecraft fused into one creative force.

Conclusion – The Mind Behind the Brush

Prince Shōtoku did not leave behind a branded “style” of Shodo in the way later masters did. Instead, his legacy lies deeper: he framed writing as a foundation for thought, governance, and spiritual practice.

Modern shodo Japanese calligraphy—from quiet temple scrolls to bold contemporary performances—still carries his influence. Every time a brush meets paper to explore meaning, identity, or faith, it echoes the insight that guided Shōtoku’s world: the written line can help shape a nation’s soul.

deepens your connection to Japanese tradition.

Explore and purchase hand-selected Japanese calligraphy artworks:

https://calligraphyartwork.stores.jp/

コメント